|

At the end of the

nineteenth century, the most distinguished

scientists and engineers declared that no

known combination of materials and locomotion

could be assembled into a practical flying

machine. Fifty years later another generation

of distinguished scientists and engineers

declared that it was technologically

infeasible for a rocket ship to reach the

moon. Nevertheless, men were getting off the

ground and out into space even while these

words were uttered.

In the last half of

the twentieth century, when technology is

advancing faster than reports can reach the

public, it is fashionable to hold the

pronouncements of yesterday's experts to

ridicule. But there is something anomalous

about the consistency with which eminent

authorities fail to recognize technological

advances even while they are being made. You

must bear in mind that these men are not

given to making public pronouncements in

haste; their conclusions are reached after

exhaustive calculations and proofs, and they

are better informed about their subject than

anyone else alive. But by and large,

revolutionary advances in technology do not

contribute to the advantage of established

experts, so they tend to believe that the

challenge cannot possibly be

realized.

The UFO phenomenon is

a perversity in the annals of revolutionary

engineering. On the one hand, public

authorities deny the existence of flying

saucers and prove their existence to be

impossible. This is just as we should expect

from established experts. But on the other

hand, people who believe that flying saucers

exist have produced findings that only tend

to prove that UFOs are technologically

infeasible by any known combination of

materials and locomotion.

There is reason to

suspect that the people who believe in the

existence of UFOs do not want to discover the

technology because it is not in the true

believer's self interest that a flying saucer

be within the

capability of human engineering. The true

believer wants to believe that UFOs are of

extraterrestrial origin because he is seeking

some kind of relief from debt and taxes by an

alliance with superhuman powers.

If anyone with

mechanical ability really wanted to know how

a saucer flies, he would study the

testimonies to learn the flight

characteristics of this craft, and then ask,

"How can we do this saucer thing?" This is

probably what Werner Von Braun said when he

decided that it was in his self-interest to

launch man into space: "How can we get this

bird off the ground, and keep it

off?"

Well, what is a

flying saucer? It is a disc-shaped craft

about thirty feet in diameter with a dome in

the center accommodating the crew and,

presumably, the operating machinery. And it

flies. So let us begin by building a

disc-shaped airfoil, mount the cockpit and

the engine under a central canopy, and see if

we can make it fly. As a matter of fact,

during World War II the United States

actually constructed a number of experimental

aircraft conforming to these specifications,

and photographs of the craft are published

from time to time in popular magazines about

science and flight. It is highly likely that

some of the UFO reports before 1950 were

sightings of these test flights. See how easy

it is when you 'want' to find answers to a

mystery?

The mythical saucer

also flies at incredible speeds. Well, the

speeds believed possible depend upon the time

and place of the observer. As stated earlier,

a hundred years ago, twenty-five miles per

hour was legally prohibited in the belief

that such a terrific velocity would endanger

human life. So replace the propeller of the

experimental disc airfoil with a modern

aerojet engine. Is mach 3 fast enough for

believers?

But the true saucer

not only flies, it also hovers. You mean like

a Hovercraft? One professional engineer

translated Ezekiel's description of heavenly

ships as a

helicopter-cum-hovercraft.

But what of the

anomalous electromagnetic effects manifest in

the space surrounding a flying saucer?

Nikola Tesla first demonstrated a prototype of an

electronic device that was eventually

developed into the electron microscope, the

television screen, an aerospace engine called

the Ion Drive. Since World War II, the

engineering of the Ion Drive has been

advanced as the most promising solution to

the propulsion of interplanetary spaceships.

The drive operates by charging atomic

particles and directing them with

electro-magnetic force as a jet to the rear,

generating a forward thrust in reaction. The

advantage of the Ion Drive over chemical

rockets is that a spaceship can sweep in the

ions it needs from its flight path, like an

aerojet sucks in air through its engines.

Therefore, the ship must carry only the fuel

it needs to generate the power for its

chargers; there is no need to carry dead

weight in the form of rocket exhaust. There

is another advantage to be derived from ion

rocketry: The top speed of a reaction engine

is limited by the ejection velocity of its

exhaust. An ion jet is close to the speed of

light, so if space travel is ever to be

practical, transport will have to achieve a

large fraction of the speed of

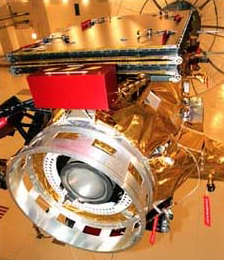

light. NASA's first ion engine was built by Glenn Research Center in 1960. Since then, ion engines have been developed by a division of Hughes Electronics Corporation, which at the time of this writing is owned by Boeing. This ion engine would be used as the primary method of propulsion in a deep space mission. The system consists of an ion thruster, power processor, and digital control and interface units.

Deep Space 1 was launched on Oct. 24, 1998 from the Cape Canaveral Air Station, the first mission in NASA's New Millennium Program. the ion engine performs the critical role of spacecraft propulsion. It is the primary method of propulsion for the 8-1/2-foot, 1,000-pound spacecraft, and its use is preparing it for possible inclusion in future NASA space science missions. "The ion propulsion engine on Deep Space 1 has now accumulated more operating time in space than any other propulsion system in the history of the space program," said John Brophy, manager of the NASA Solar Electric Propulsion Technology Applications Readiness project, at the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif.

Unlike the fireworks of most chemical rockets using solid or liquid fuels, the ion drive emits only an eerie blue glow as ionized (electrically charged) atoms of xenon are pushed out of the engine. Xenon is the same gas found in photo flash tubes and many lighthouse bulbs. Carrying about 81.5 kilograms (179.7 lbs) of xenon propellant, the Deep Space 1 ion engine had a total operating time of more than 583 days (14,000 hours) and traveled over 200 million miles at the time of its retirement in December of 2001. A photo of the Deep Space 1 Ion engine can be viewed below.

In 1972 the French

journal Science et Avenir reported

Franco-American research into a method of

ionizing the airstream flowing over the wings

to eliminate sonic boom, a serious objection

to the commercial success of the Concorde.

Four years later a picture appeared in an

American tabloid of a model aircraft showing

the current state of development. The

photograph shows a disc-shaped craft, but not

so thin as a saucer; it looks more like a

flying curling stone. In silent flight, the

ionized air flowing around the craft glows as

a proper ufo should. The last word comes from

an engineering professor at the local

university; he has begun construction of a

flying saucer in his backyard.

There are three basic

types of locomotion engines. The primary

type is traction. The foot and the wheel

are traction-type engines. Traction engines

depend upon friction against a surrounding

medium to generate movement, and locomotion

can proceed only as far and as speedily as

the surrounding friction will provide. The

second type of locomotion engine is displacement. The balloon

and the submarine rise by displacing a denser

medium; they descend by displacing less that

their weight. The third type of engine is the

rocket engine. A rocket is driven by reaction

from the mass of material it ejects. Although

a rocket is most efficient when not impeded

by a surrounding medium, it must carry not

only it's fuel, but also the mass it must

eject for propulsion. As a consequence, the rocket is

impractical where powerful acceleration is

required for extended distances. In chemical

rocketry, ten minutes is a long burn for

powered flight. What is needed for practical

antigravity locomotion is a fourth type of locomotion

which does not depend upon a surrounding

medium or ejection of mass.

You must take notice

that none of the principles of locomotion

required any new discovery. They have all

been around for thousands of years, and

engineering only implemented the principle

with increasing efficiency. A fourth

principle of locomotion has also been around

for thousands of years: It is centrifugal

force. Centrifugal force is the principle of

the military sling and the medieval

catapult.

Everyone knows that

centrifugal force can overcome gravity. If

directed upward, centrifugal force can be

used to drive an antigravity engine. The

problem engineers have been unable to solve

is that centrifugal force is generated in all

directions on the plane of the centrifuge. It

won't provide locomotion unless the force can

be concentrated in one direction. The

solution of the sling, of releasing the

wheeling at the instant the

centrifugal force

is directed along the ballistic trajectory,

has all the inefficiencies of a cannon. The

difficulty of the problem is not real,

however. There is a mental block preventing

people from perceiving a centrifuge as

anything other than a flywheel.

A bicycle wheel is a

flywheel. If you remove the rim and tire,

leaving only the spokes sticking out of the

hub, you still have a flywheel. In fact,

spokes alone make a more efficient flywheel

than the complete wheel; this is because

momentum goes up only in proportion to

mass but with the square of speed. Spokes are

made of drawn steel with extreme tensile

strength, so spokes alone can generate the

highest level of centrifugal force long after

the rim and tire have disintegrated. But

spokes alone still generate centrifugal force

equally in all directions from the plane of

rotation. All you have to do to concentrate

centrifugal force in one direction is remove

all the spokes but one. That one spoke still

functions as a flywheel, even though it is

not a wheel any longer.

See how easy it is

once you accept an attitude of solving one

problem at a time as you come to it? You can

even add a weight to the end of the spoke to

increase the centrifugal force.

But our centrifuge

still generates a centrifugal force

acceleration in all directions around the

plane of rotation even though it doesn't

generate acceleration equally in all

directions at the same time. All we have

managed to do is make the whole ball of wire

wobble around the common center of mass

between the axle and free end of the spoke.

To solve this problem, now that we have come

to it, we need merely to accelerate the spoke

through a few degrees of arc and then let it

complete the cycle of revolution without

power. As long as it is accelerated during

the same arc at each cycle, the locomotive

will lurch in one direction, albeit

intermittently. But don't forget that the

piston engine also drives intermittently. The

regular centrifugal pulses can be evened out

by mounting several centrifuges on the same

axle so that a pulse from another flywheel

takes over as soon as one pulse of power is

past it's arc.

The next problem

facing us is that the momentum imparted to

the centrifugal spoke that carries it all

around the cycle with little loss of

velocity. The amount of concentrated

centrifugal force carrying the engine in the

desired direction is too low to be practical.

Momentum is half the product of mass

multiplied by velocity squared. Therefore,

what we need is a spoke that has a tremendous

velocity with minimal mass. They don't make

spokes like that for bicycle wheels. A search

through the engineers' catalog however, turns

up just the kind of centrifuge we need. An

electron has no mass at rest (you cannot find

a smaller minimum mass than that); all it's

mass is inherent in its velocity. So we build

an electron raceway in the shape of a

doughnut in which we can accelerate an

electron to a speed close to that of light.

As the speed of light is approached, the

energy of acceleration is converted to a

momentum approaching infinity. As it happens,

an electron accelerator answering our need

was developed by the University of California

during the last years of World War II. It is

called a betatron, and the doughnut is small

enough to be carried comfortably in a man's

hands.

We can visualize the

operation of the Mark I from what is known

about particle accelerators. To begin with,

high energy electrons ionize the air

surrounding them. This causes the betatrons

to glow like an annular neon tube.

Therefore, around the

rim of the saucer a ring of lights will glow

like a string of shining beads at night. The

power required for flight will ionize enough

of the surrounding atmosphere to short out

all electrical wiring in the vicinity unless

it is specially shielded. In theory, the top

speed of the Mark I is close to the speed of

light; in practice there are many more

problems to be solved before relativistic

speeds can be approached.

The peculiar property

of microwaves heating all material containing

the water molecule means that any animal

luckless enough to be nearby may be cooked

from the inside out; vegetation will be

scorched where a saucer lands; and any rocks

containing water of crystallization will be

blasted. Every housewife with a microwave

knows all this; only hard-headed scientists

and soft-headed true believers are completely

dumbfounded. The UFOnauts would be cooked by

their own engines, too, if they left the

flight deck without shielding. This probably

explains why a pair of UFOnauts, in a widely

published photograph, wear reflective plastic

jumpsuits. Mounting the betatrons outboard on

a disc is an efficient way to get them away

from the crew's compartment, and the plating

of the hull shields the interior. At high

accelerations, increasing amounts of power

are transformed into radiation, making the

centrifugal drive inefficient in strong

gravitational fields. The most practical

employment of this engineering is for large

spacecraft, never intended to land. The

flying saucers we see are very likely

scouting craft sent from mother ships moored

in orbit. For brief periods of operation, the

heavy fuel consumption of the Mark I can be

tolerated, along with radiation leakage -

especially when the planet being scouted is

not your own.

When you compare the

known operating features of particle

centrifuges with the eyewitness testimony, it

is fairly evident that any expert claiming

flying saucers to be utterly beyond any human

explanation is not doing his homework, and he

should be reexamined for his professional

license.

For dramatic purpose,

I have classified the development of the

flying saucer through five stages:

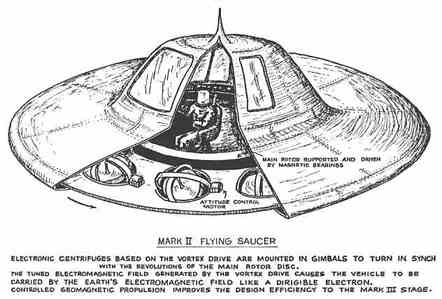

Mark I - Electronic

centrifuges mounted around a fixed disc,

outboard. Mark II - Electronic centrifuges

mounted outboard around a rotating disc. Mark

III - Electronic centrifuges mounted outboard

around a rotating disc, period of cycles

tuned to harmonize with ley lines, for jet

assist. Mark IV - Particle centrifuge tuned

to modify time coordinates by faster than

light travel. Mark V - No centrifuge. Solid

state coils and crystal harmonics transforms

ambient field directly for dematerialization

and rematerialization at destinations in time

and space.

Now that the UFO

phenomenon has been demystified and reduced

to human ken, we can proceed to prove the

theory. If your resources are like those of

the PLO, you can go ahead and build your own

flying saucer without any further information

from me, but I have nothing to work with

except the junk I can find around the

house.

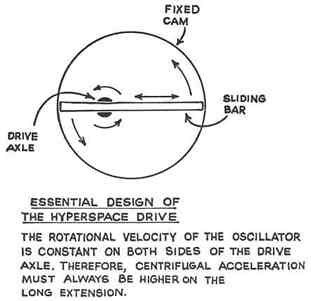

I found an old

electric motor that had burned out, but still

had a few turns left in it. I drilled a hole

through the driving axle so that an eight

inch bar would slide freely through it. I

mounted the motor on a chassis so that the

bar would rotate on an eccentric cam. In this

way in end of the bar was always extended in

the same direction while the other end was

always pressed into the driving axle. As both

ends had the same angular velocity at all

times, the end extending out from the axle

would always have a higher angular momentum.

This resulted in a concentration of

centrifugal acceleration in one direction.

When I plugged in the motor, the sight of my

brainchild lurching ahead - unsteadily, but

in a constant direction, - gave me a bigger

thrill than my baptism of sex - lasted

longer, too. But not much longer. In less

than twenty seconds the burned-out motor

gasped its last and died in a puff of smoke;

the test run was broadcast on radio

microphone but the spectacle was lost without

television. Because my prototype did not

survive long enough to run in two directions

I had to declare the test inconclusive

because of mechanical breakdown. So, what the

hell, the Wright brothers didn't get far off

the ground the first time they tried either.

Now that I know the critter will move, it is

worthwhile to put a few bucks in to a new

motor, install a clutch, and gear the

transmission down. One problem at a time is

the way it goes.

A rectified

centrifuge small enough to hold in one hand

and powered by solar cells, based on my

design, could be manufactured for about fifty

dollars (depending on production and

competitive bids). Installed on Skylab, it

would be sufficient to keep the craft in

orbit indefinitely. A larger Hyperspace Drive

(as I call this particular design) will

provide a small but constant acceleration for

interplanetary spacecraft that would

accumulate practical velocities over runs of

several days.

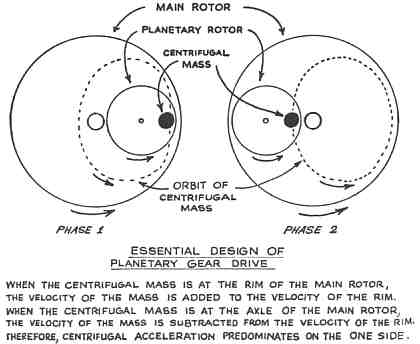

It is rumored that a

gentleman by the name of D. invented another

kind of antigravity engine sometime during

the past fifty years, but I have been unable

to track down any more information except

that its design consists of wheels within

wheels. I've heard of another gentleman in Florida, Hans

Schnebel, who described a machine

he built and tested that is similar in

principle to the D. drive. Essentially, a

large rotating disk has a smaller rotating

disc on one side of the main driving axle.

The two wheels are geared together so that a

weight mounted on the rim of the smaller

wheel is always at the outside of the larger

wheel during the same length of arc of each

revolution, and always next to the main axle

during the opposite arc. What happens is that

the velocity of the weight is amplified by

harmonic coincidence with the large rotor

during one half of its period of revolution,

and diminished during the other half cycle.

This concentrates momentum in the same

quarter continually, to rectify the

centrifuge. The result is identical to my

Hyperspace Drive, but has the beauty of

continuously rotating motion. Now, if the D.

drive is made with a huge main rotor, - like

about thirty feet in diameter - there is

enough room to mount a series of smaller

wheels around the rim, set in gimbals

for attitude control, an

Mr. D. himself has himself a model T Flying

Saucer requiring no license from the

AEC.

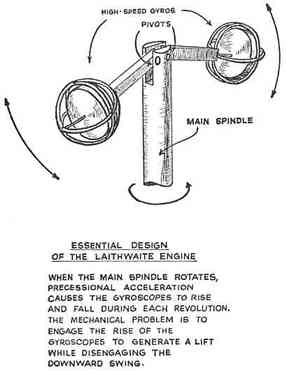

In 1975, Professor E.

Laithwaite, Head of the Department of Electrical

Engineering at the Imperial College of

Science and Technology in London, England,

invented another approach to harnessing the

centrifugal force of a gyroscope to power an

antigravity engine - well, he almost invented

it, but he did not have the sense to hold

onto success when he grasped it. Professor L.

is world-renowned for his most creative

solutions to the problems of

magnetic-levitation-propulsion systems, and

the fruit of his brain is operating today in

Germany and Japan, his railway trains float

in the air while traveling at over three

hundred miles per hour. If anyone can present

the world with a proven anti gravity engine,

it must be the professor.

L. satisfied himself

that the precessional force causing a

gyroscope to wobble had no reaction. This is

a clear violation of Newton's Third Law of Motion

as 'generally conceived'. L. figured that if

he could engage the precessional acceleration

while the gyroscope wobbled in one direction

and release the precession while it wobble in

other directions, he would be able to

demonstrate to a forum of colleagues and

critics at the college a rectified centrifuge

that worked as a proper antigravity engine.

His insight was sound but he did not work it

out right. All he succeeded in demonstrating

was a 'separation between action and

reaction,' and his engine did nothing but

oscillate violently. Unfortunately, neither

L. or his critics were looking for a temporal

separation between action and reaction, so

the loophole he proved in Newton's Third Law was

not noticed. Everyone was looking for action

without reaction, so no one saw anything at

all. Innumerable other inventors have

constructed engines essentially identical to

L.'s, including a young high school dropout

who lives across the street from

me.

Another invention

described is U.S. Patent disclosure number

3,653,269, granted to R. F., a retired

chemical engineer in Louisiana. F. mounted

his gyroscopes around the rim of a large

rotor disc, like a two cylinder flying

saucer. Every time the rotor turns a half

cycle, the precessional twist of the gyros in

reaction generates a powerful force. During

the half cycle when F.'s gyros were twisting

in the other direction, his clutch grabbed

and transmitted the power to the driving

wheels. During the other half cycle, the

gyros twisted freely. F. claims his machine

traveled four miles per hour until it flew to

pieces from centrifugal forces. After

examining the patents, I agreed that it

looked like it would work, and it certainly

would fly to pieces because the bearing

mounts were not nearly strong enough to

contain the powerful twisting forces his

machine generated. F.'s design, however,

cannot be included among antigravity engines

because it would not operate off the ground.

He never claimed it would, and F. always

described his invention truthfully as nothing

more than an implementation of the fourth

principle of locomotion.

What L. needed was

another rotary component, like the D. drive,

geared to his engine's oscillations so that

they would always be turned to drive in the

same direction. As it happens, an Italian by

the name of Todeschini recently secured a

patent on this idea,

and his working model is said to be

attracting the interest of European

engineers.

When the final

rectifying device is added to the essential

L. design, all the moving parts generate the

vectors of a vortex, and the velocity

generated is the axial thrust of the vortex.

Therefore I call inventions based on this

design the Vortex Drive.

By replacing the

Hyperspace modules of the Mark I Flying

Saucer with Vortex modules, still retaining

the essential betatron as the centrifuge,

performance is improved for the Mark II. To

begin with, drive is generated only when the

main rotor is revolving, so the saucer can be

parked with the motor running. This

eliminates the agonizing doubt we all

suffered when the Lunar Landers were about to

blast off to rejoin the command capsule: Will

the engine start? This would explain why the

ring of lights around the rim of a saucer is

said to begin to revolve immediately prior to

lift off. A precessional drive affords a

wider range of control, and the responses are

more stable than a direct centrifuge. But the

most interesting improvement is the result of

the 'structure' of the electromagnetic field

generated by the Vortex drive. By amplifying

and diminishing certain vectors harmonically,

the Mark III flying saucer can ride the

electromagnetic current of the Earth's

electromagnetic field like the jet stream.

And this is just what we see UFO's doing,

don't we, as they are reported running their

regular flight corridors during the biennial

tourist season. Professor L. got all this

together when he conceived of his antigravity

engine as a practical application of his

theory of "rivers of energy running through

space"; he just could not get it off the

drawing board the first time.

The flying saucer

consumes fuel at a rate that cannot be

supplied by all the wells in Arabia.

Therefore we have to assume that UFO

engineers must have developed a practical

atomic fusion reactor. But once the Mark III

is perfected, another fuel supply becomes

attainable, and no other is so practical for

flying saucer. The Moray Valve converts the

Mark III into a Mark IV Flying Saucer by

extending its operational capabilities

through 'time' as well as space. The Moray

Valve, you see, functions by changing the

direction of flow of energy in the Sun's

gravitational field. It is the velocity of

energy that determines motion, and motion

determines the flow of time. We shall

continue the engineering of flying saucers in

the following essays.

My investigation into

antigravity engineering brought me a

technical report while this typescript was in

preparation. Dr. M. R., President of the

University for Social Research, published a

paper describing the discoveries of Dr. P. A.

Biefeld, astronomer and physicist at the

California Institute for Advanced Studies,

and his assistant, T. B.. In 1923 Biefeld

discovered that a heavily charged electrical

condensor moved toward its positive pole when

suspended in a gravitational field. He

assigned B. to study the effect as a research

project. A series of experiments showed B.

that the most efficient shape for a field

propelled condensor was a disc with a central

dome. In 1926 T. published his paper

describing all the construction features and

flight characteristics of a flying saucer,

conforming to the testimony of the first

flight witnessed over Mount Rainer

twenty-one years later

and corroborated by thousands of witnesses

since. (The Biefeld-Brown Effect explains why

a Mark III rides the electromagnetic jet

stream.)

One can speculate that

flying saucers spotted from time to time may

not only include visitors from other planets

and travelers through time, but also aviators

and/or scientists from a number of secret

experimental aircraft plants around the world.

Top

Order CLARK and SACAJAWEA - the Untold Love Story

|

![]()